The Echo of Unspoken Words

お元気ですか?おげんきですか?o-genki desu ka?How are you? — 私は元気です。わたしはげんきです。watashi wa genki desuI am fine.

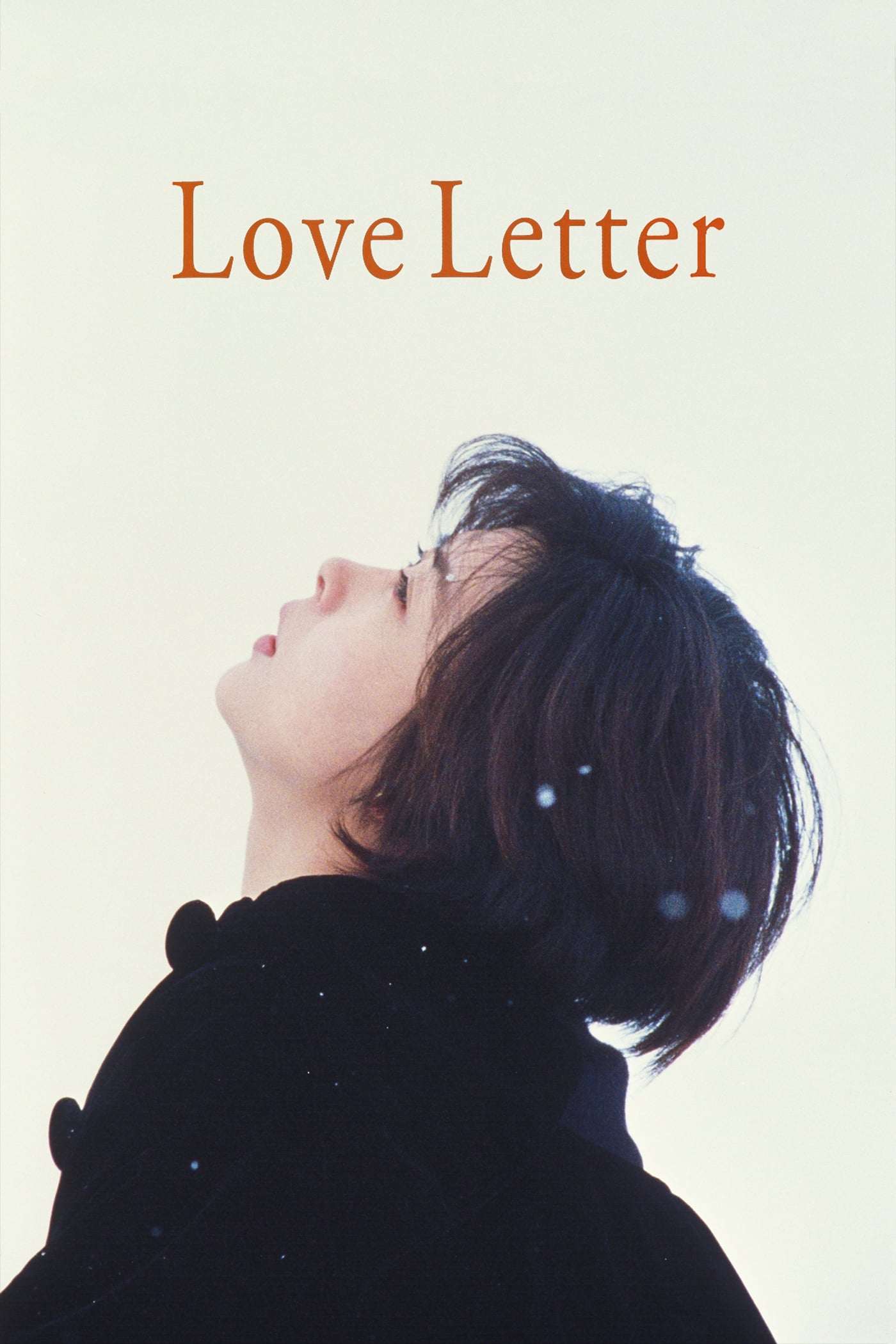

There’s something about Shunji Iwai’s Love Letter that lingers. Released in 1995, it arrived during a period when Japanese cinema was quietly moving away from the more aggressive urban narratives of the bubble era. Instead, Iwai turned inward, toward Otaru’s snow-covered streets and the peculiar grief that refuses to announce itself loudly.

The Mechanism of Memory

The film starts with an act that borders on irrational: Hiroko Watanabe writes to her dead fiancé. She addresses the letter to his childhood home, which shouldn’t exist anymore. But someone writes back, a woman, also named Itsuki Fujii. What follows isn’t really a mystery in the traditional sense. It’s more like watching someone try to reconstruct a person from scraps: a library card here, a pencil sketch there, letters that were never actually meant for you.

Iwai seems interested in how we construct the people we love, how much of them is actually them and how much is just our own need projected onto whatever evidence remains. The two Itsukis, one dead, one alive, create this weird mirror where identity starts to blur at the edges.

What the Camera Does

The soft focus isn’t just aesthetic posturing. Iwai shoots like he’s replicating what it feels like to remember something, that sensation where you can feel a moment intensely but can’t quite see it clearly anymore. Everything has this quality of 懐かしいなつかしいnatsukashiinostalgia, that specifically Japanese nostalgia that’s less about wanting to return to the past and more about acknowledging that certain feelings can only exist in retrospect.

The natural lighting does something similar. Scenes feel like they’re already halfway to becoming memories while you’re watching them.

Space as Emotional Architecture

What struck me most on rewatches is how Iwai uses location. The library, the mountains, the clinic, these aren’t just backdrops. They’re containers that hold history, places the characters have to physically move through to get anywhere emotionally.

That scene where Hiroko shouts into the mountains could’ve been melodramatic. Instead it feels necessary, like she’s finally addressing the fact that the landscape has swallowed the person she loved. She’s literally trying to fill a void with sound, knowing full well it won’t work. It’s a ritual, not a solution.

The Work of Forgetting

Most romance films are about people coming together. Love Letter is about the exhausting work of letting go. Love here functions almost like detective work, you dig through evidence, follow leads, interview witnesses. But what you discover tells you as much about yourself as it does about the person you’re investigating.

The film suggests that grief isn’t just about absence. It’s about realizing that the person you’re mourning might have been a composite all along, built from your interpretations and projections. And maybe that’s okay. Maybe that’s just what love is.

Why It Holds Up

Love Letter doesn’t offer easy comfort. It’s not interested in closure as a concept. Instead, it sits with the uncomfortable truth that we haunt ourselves, that the past doesn’t resolve neatly, and that sometimes understanding comes too late to matter in any practical sense.

But there’s something almost generous in how Iwai films all of this, the way he lets scenes breathe, the way he trusts the audience to sit with ambiguity. It’s a film about what remains when intensity fades: not nothing, but not everything either. Just echoes, and the strange comfort of knowing someone else heard them too.